Stereax Field Trial at the Offshore Renewable Energy (ORE) Catapult

Posted on: in Blog

Stereax Field Trial at the Offshore Renewable Energy (ORE) Catapult

With increasing global concern about climate change, energy companies are looking to offer more renewable, clean sources of energy in order to meet the targets of the Paris Agreement. Wind energy is seen as a sustainable and eco-friendly solution and a recent report suggested the global offshore wind turbine market will increase 22.5% from 2018 to 2025 with annual revenue rising to $30.5 bn, representing 4.8% worldwide electricity usage at the end of 2019.

Key to the success of offshore wind as an energy source is ensuring that wind turbines work efficiently. Whilst the number of wind turbines is rapidly increasing, providing the world with 600 GWh of renewable energy every year, the repair of turbine blades is very costly due to the difficulty of accessing the blades themselves: an average blade repair can cost up to $30,000 and a new blade costs, on average, about $200,000.

Real-time monitoring of the blade’s health can help to avoid catastrophic events caused by delamination, cracks, impact or ice. However, if these sensors are hard-wired, placing many sensors on blades, which may be as long as 80m, is difficult and could be disruptive to the blade’s function and stability. Moreover, hard-wiring of sensors on blades is not only difficult but inadvisable because of the increased likelihood of a lightning strike. Fibre optic connections are also possible but expensive. Hence a wireless, battery-powered solution has distinct advantages. However, frequent replacement of batteries has environmental and cost implications, so a key feature of the batteries must be long-life. Also, due to the hostile location, these batteries need to operate at low and high temperatures in a high vibration environment.

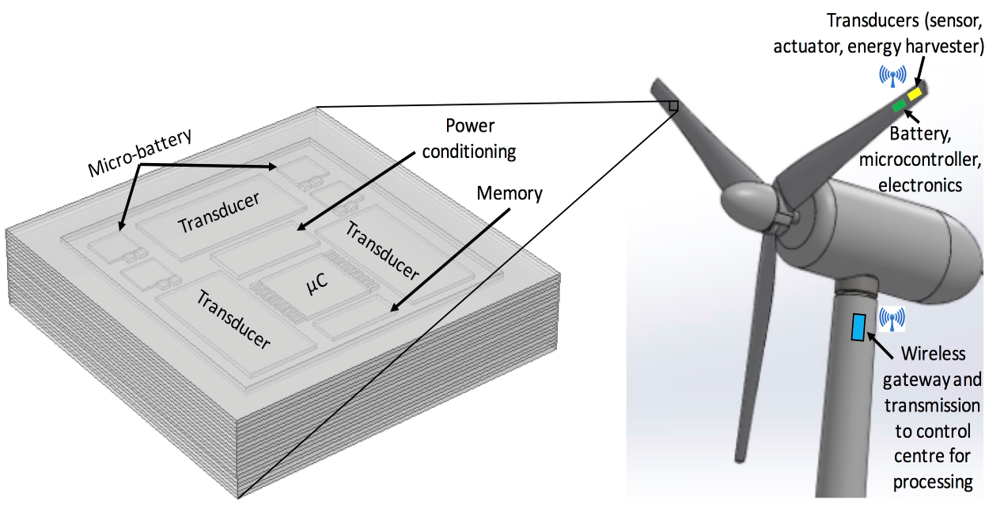

At Ilika, we’ve been developing an integrated smart sensor - powered by a combined vibration harvester and a Stereax solid state battery – which can be installed in wind turbine blades. The development of this device was carried out in partnership with University of Chester Smart Composite Group led by Prof Yu Shi and Prof Yu Jia at University of Aston and funded by Innovate UK as "Project SmartBlade". Following 20 months of development with our partners, we then undertook a field trial to test the ability of this device to autonomously power sensors on a real turbine blade, Figure 1.

The field trial took place over two days in January 2020 at the Offshore Renewable Energy (ORE) Catapult’s National Renewable Energy Centre in Blyth, Northumberland. The facility holds a 40m long blade that is used to study the physical constraints placed on such a large construction with the aim of informing new, innovative blade designs, Figure 2.

We collaborated with ORE Catapult engineers in order to understand two things:

- Can the constant vibration of the blade (which would be wind-induced in the field) be turned into electrical energy which can charge a battery and power the sensing device? If this works, the sensing device won’t need to be powered with cables and could be powered off rechargeable batteries or capacitors.

- Can we use the way the blades vibrate to provide an indication about their health and transmit that information wirelessly (using long-range LoRa protocol)? The advantage of wind is that it rotates blades to create electricity, but its disadvantage is that it also shakes and bends the blades, sometimes by 5-6 meters at the tip. This creates stresses in the blade’s structure which can eventually lead to delamination and cracking.

Wind turbine blades are hollow with enough space at their root for a person to stand inside. This internal cavity is the best place to fit any sensors and other electronics rather than putting them on the outside of the blade where they could disrupt the aerodynamics. Despite this level of protection, the sensing solution still needs to withstand hostile environmental conditions.

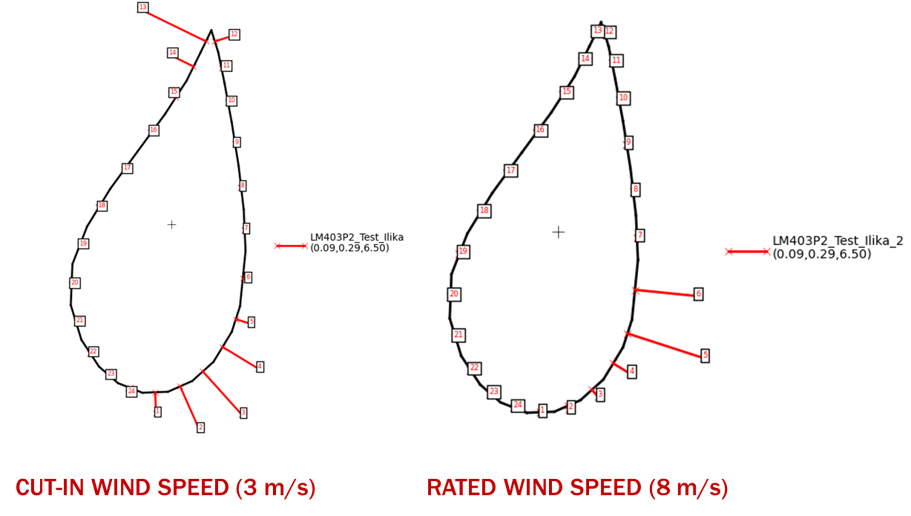

The first step of the study was to determine which parts of the blade deliver strain that can be harvested under rated wind strength conditions so as to optimise our chance of getting maximum energy in our battery. The ORE Catapult engineers modelled this strain data (Figure 3) and advised us to take measurements in a section 6.5 m away from the blade root and 2.6 m away from the trailing edge, as shown in Figure 4.

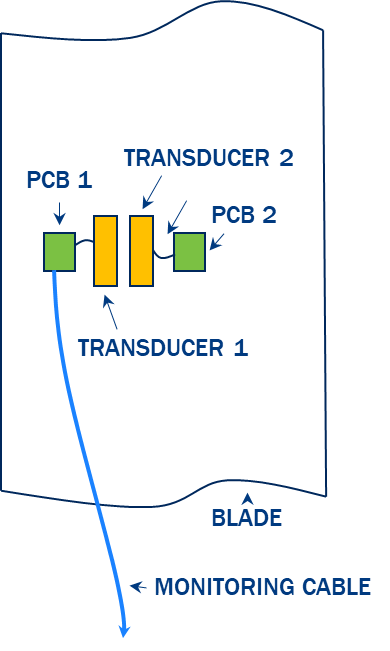

As we wanted to test two things, we built and tested two prototype sensors each with different functions, as shown in Figure 5:

Sensor 1 consists of two parts:

- TRANSDUCER 1: Has the function of harvesting vibration energy

- Printed Circuit Board PCB1: Monitors the charging of a battery from the harvested energy from TRANSDUCER 1

Sensor 2 also has two sections:

- TRANSDUCER 2: Capture vibration data from the moving blade

- PCB2 transmits the data wirelessly

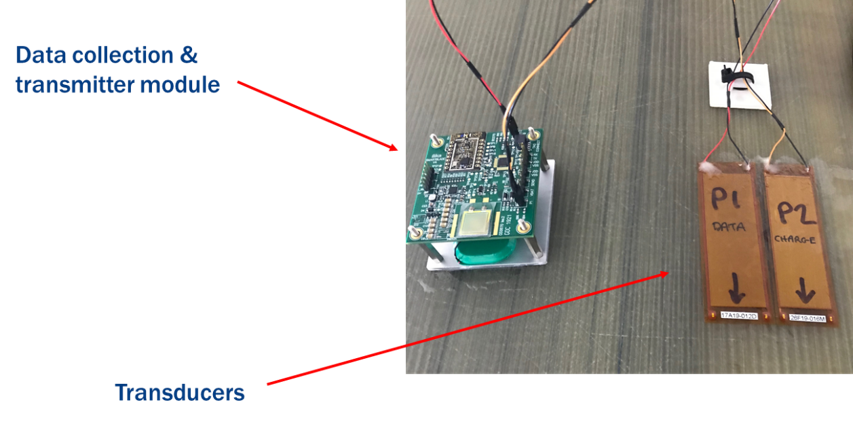

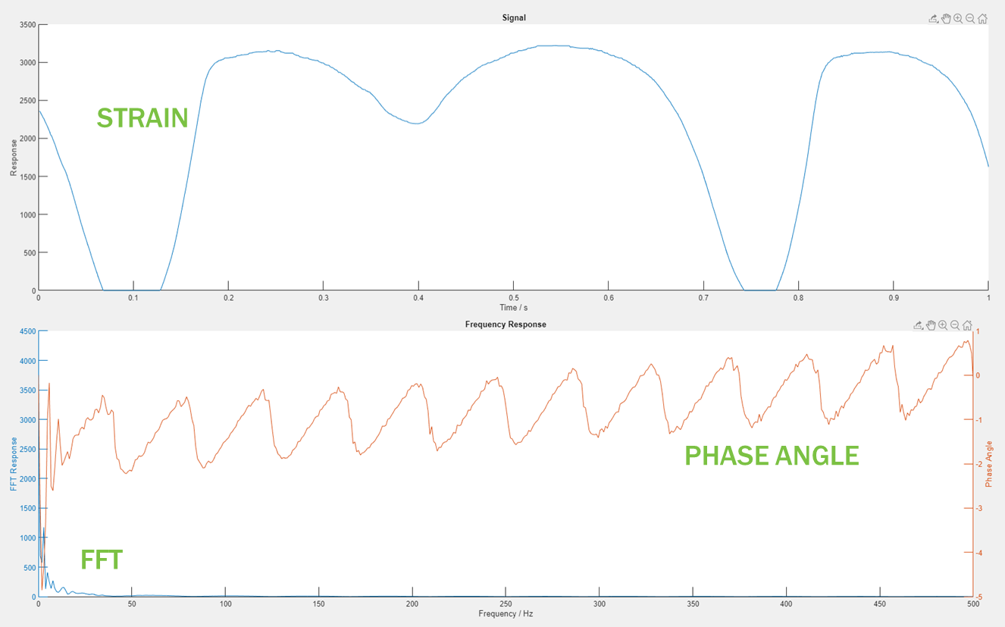

The transducers are pieces of Macro Fiber Composite (MFC) which can produce electricity when bent (piezoelectricity). In this study, the transducers have two functions, Figure 6: first they create electrical energy to charge the battery; second they can send an electrical signal (strain data) containing a signature about its health. The frequency spectrum generated by Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) of the strain data has peaks that change frequency when cracks or delamination occur.

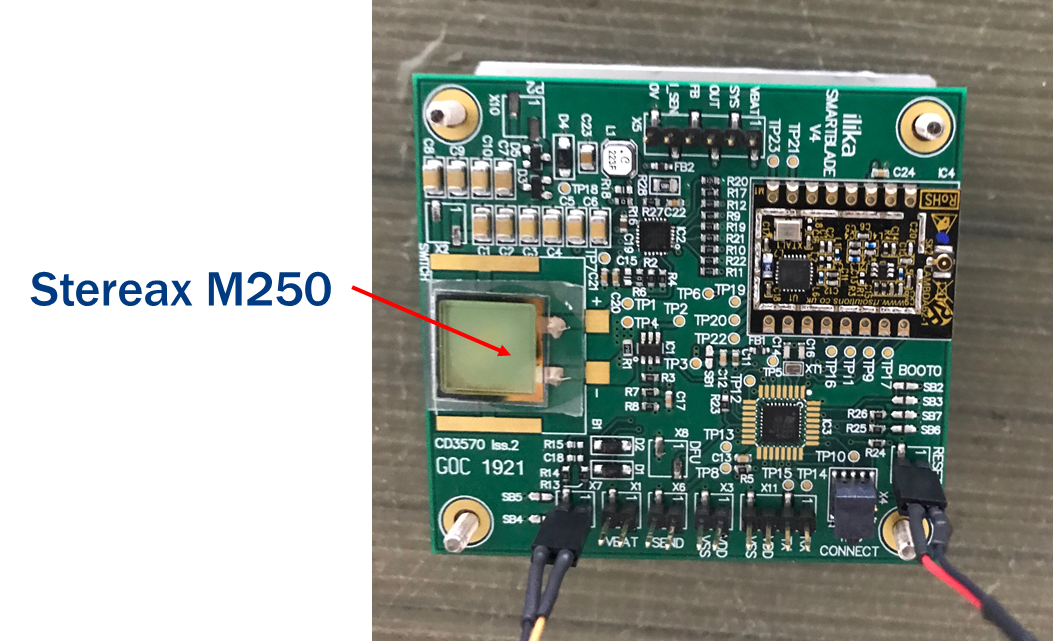

The Printed Circuit Board (PCB) consists of the main electronic components, Figure 7:

- A LoRa wireless communication module. LoRa was preferred to Bluetooth Low Energy as a communication protocol due to its longer range and ability to transmit through the blade material without significant attenuation. In a real-environment, the communication module would send the data collected by the transducers to a larger, non-mobile unit on the turbine mast which could carry out calculations and transmit its information via the cloud to engineers operating in the wind turbine field.

- A Stereax M250 solid state battery and additional passive components which operate the device: it is vital the device continues working even if there is no wind, so a small, thin but long life battery is required to store energy in greatly changing temperatures. A large battery would potentially start interfering with the operation of the blade and a battery with a lifespan of only a year or so would incur substantial operational costs – not only downtime caused by stopping the wind turbine but also manpower cost of an engineer travelling offshore to climb the tower and inside the blade.

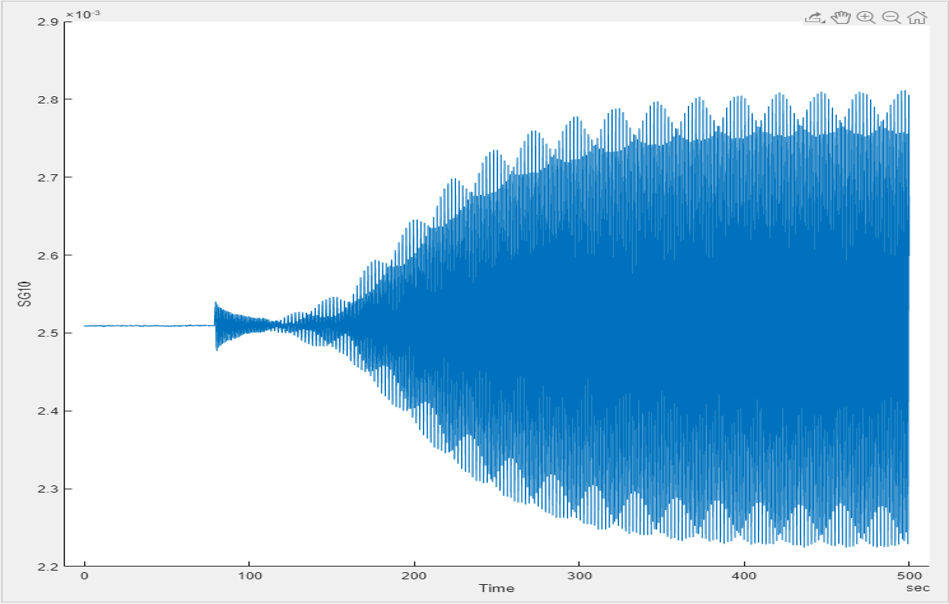

During the study, we placed our prototype sensors at the advised position, the ORE Catapult engineers then placed six 500 kg weights on the blade and started to “excite” the blade to mimic what would happen offshore under a wind of 8 m/s. The generated data are shown in Figure 8 and Figure 9.

So, what did we learn? Under vibrations equivalent to a wind speed of 8 m/s the battery can be fully charged in under five hours. Lab tests have shown that energy generated is highly dependent on vibration frequency, so this value is surprisingly high, considering the low vibrations frequencies measured. This shows that enough energy could be harvested to the device from wind-induced vibrations for a 10-minute cycle. i.e. strain data can be measured and communicated via the LoRa wireless module every 10 minutes. In reality such measurements don’t need to take place every 10 minutes because structural damage to a blade happens over hours and days rather than minutes. However real-time “in-situ” measurements can give an indication in advance of when a blade is potentially going to fail, enabling the fault to be fixed as soon as possible and avoiding costly downtime.

The result of this study was that it successful validated our concept of a sensing device that can be powered autonomously for a long time by harvesting energy from wind-induced vibrations. If you’d like to find out more about how our technology can help the condition monitoring of your wind turbines and blades, or perhaps in other related applications, contact us now at info@ilika.com.

Learn more about Stereax solid state batteries here